By Marco Scarci, Consultant Thoracic Surgeon

Lung cancer surgery is often assumed to be the first step, but most people don’t realize that some of the most important decisions I make are the ones where I say “no.”

This is a real case from my practice — fully anonymised — where a patient was referred to me for lung-cancer surgery, and I declined to operate. I’ll walk you through the CT images, the clinical reasoning, and what actually happened next.

My goal is simple: to show you what surgeons usually don’t, and to help you understand how these decisions truly work.

The Referral: ‘Fit for Surgery and Motivated’

A patient in their 60s was referred with a 2.2cm lesion in the upper lobe of the right lung.

The initial summary said:

- “Suspicious nodule”

- “No significant spread”

- “Likely candidate for VATS lobectomy”

On paper? Straightforward.

But imaging always tells the real story.

The Scan That Changed Everything

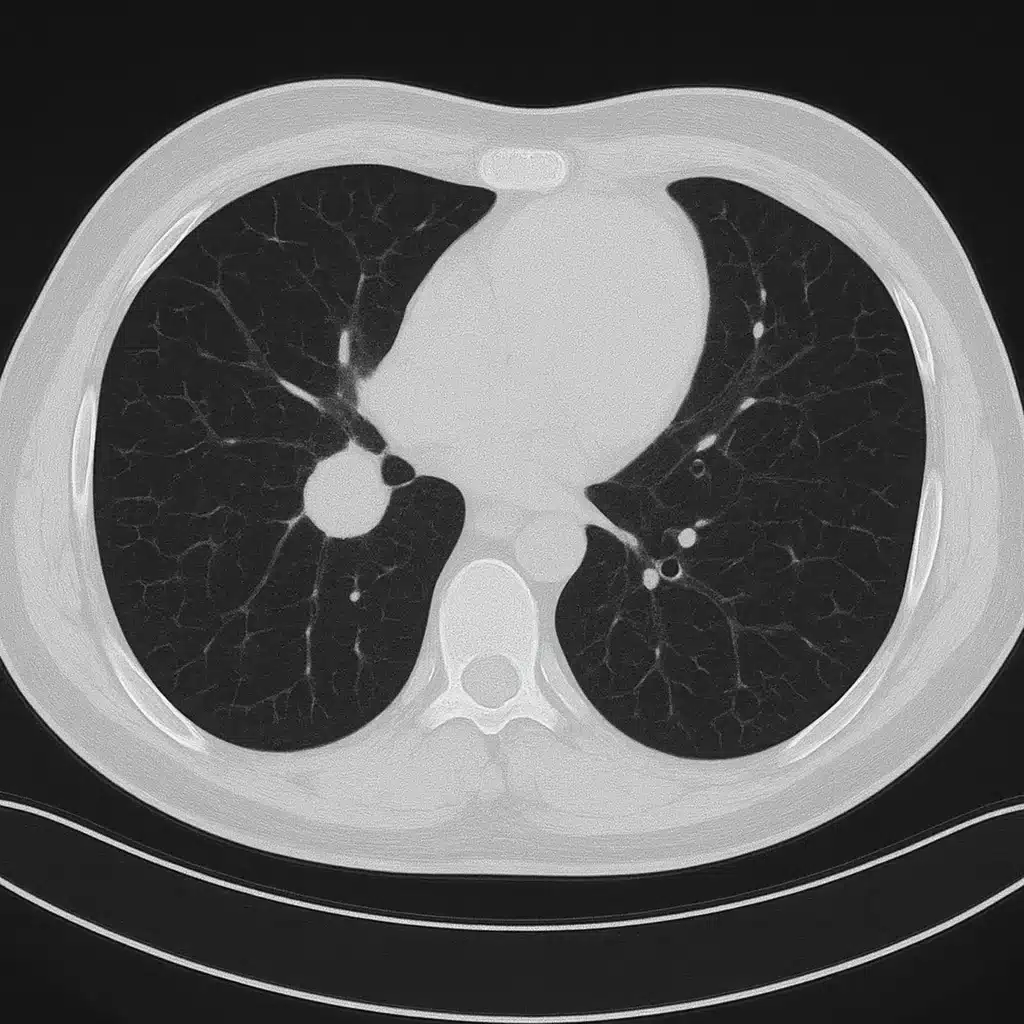

CT Finding #1: The Nodule Wasn’t Sitting Cleanly

On first look the tumour seemed operable.

On closer inspection, the lesion appeared broad-based against the mediastinum, making dissection riskier and raising suspicion of early invasion.

This alone doesn’t cancel surgery — but it raises the stakes.

CT Finding #2: A ‘Minor’ Lymph Node That Wasn’t Minor

A 1.1cm hilar lymph node looked enlarged but was labelled “likely reactive.”

In thoracic surgery, a single centimetre can be the difference between:

- curative surgery

- and a major, unnecessary operation with no benefit.

This had to be investigated further.

CT Finding #3: Hidden Emphysema

The patient’s lung function tests were borderline normal.

But the CT revealed patches of emphysema that would make post-lobectomy breathing significantly harder than the numbers suggested.

This is one of those things that rarely gets mentioned in public writing about thoracic surgery — test results don’t always reflect reality.

The Decision: Why I Said No

After MDT discussion and further PET imaging, the lymph node lit up clearly.

This changed the patient’s stage and meant a lobectomy would almost certainly not be curative, would bring high risk, and would delay the systemic treatment they actually needed.

Operating would have:

– removed functional lung

– exposed them to major surgical risk

– provided no survival benefit

– delayed correct therapy by 4–6 weeks

So I told the patient something many surgeons avoid saying:

“You don’t need surgery — you need treatment that actually helps you live longer.”

They started on chemo-immunotherapy within two weeks.

Patient Outcome After Declining Lung Cancer Surgery

Six months later, the node had shrunk significantly and the primary tumour reduced in size.

The patient maintained good quality of life and normal daily activity.

Would a lobectomy have achieved this?

No — it would have harmed them, not helped.

Why I’m Sharing This Lung Cancer Surgery Case

Patients rarely get to see how surgical decisions are made.

Most blogs and videos in my speciality show only:

- impressive key-hole techniques

- dramatic before/after images

- stories of successful operations

But the cases I don’t operate on are just as important.

Sometimes more.

So here’s the rule I live by:

If surgery won’t improve survival, safety, or quality of life — I don’t do it.

Even if it’s technically possible.

Even if the referral expects it.

Even if it’s profitable.

Not all cancers need a knife.

What every patient does need is honesty.

A Quick Note on Patient Privacy

All patient details, images, and timelines have been anonymised and altered to protect identity, in line with UK GMC guidelines and patient-confidentiality standards.