So, what actually causes a sunken chest? Many people wonder if it's due to an injury or something they did, but the truth lies in how the body itself grows. The primary cause of pectus excavatum is the abnormal and accelerated growth of the cartilage that connects your ribs to your breastbone.

This overgrowth pushes the sternum (breastbone) inwards, creating that distinctive sunken look.

What Is the Main Cause of Pectus Excavatum

At the heart of pectus excavatum is a developmental issue with the costal cartilages – the flexible bits of tissue that join your ribs to your sternum.

Think of it like the support beams of a bridge growing too long and too fast for the structure they're meant to hold. Instead of lying flat and stable, they start to buckle under the strain, pulling the centre of the bridge downwards. That’s a pretty good analogy for what happens inside the chest.

This excessive growth puts constant inward pressure on the sternum. Over time, this force pushes the breastbone back towards the spine, resulting in a chest that looks caved-in or hollowed out.

The Role of Growth Spurts

While pectus excavatum can sometimes be spotted at birth or in early childhood, it often becomes much more obvious during the teenage growth spurt.

This is a really common pattern we see. The deformity can go from being mild to quite severe in a short space of time, typically around the ages of 11 to 14 when kids are hitting puberty. The same hormonal surges that drive that rapid increase in height unfortunately also fuel the overgrowth of the costal cartilages.

You can learn more about how the condition presents by exploring the different types of chest wall deformities.

The crucial thing to understand is that pectus excavatum is a structural, developmental condition. It’s not caused by external factors like slouching or certain activities. The issue is rooted in the body's own growth processes.

Unpacking the Underlying Factors

While we know cartilage overgrowth is the direct mechanical cause, the "why" behind it is a bit more complex. Most experts agree that it’s a multifactorial condition, meaning several elements are likely at play.

Here's a closer look at the key factors thought to be involved:

| Key Factors Contributing to Pectus Excavatum | |

|---|---|

| Factor | Description |

| Genetic Predisposition | The condition often runs in families. If a parent or sibling has it, the chances of another family member developing it are significantly higher. This points to a strong inherited component, although the specific genes haven't all been identified. |

| Connective Tissue Disorders | Pectus excavatum is frequently seen alongside conditions that affect the body's connective tissues, such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. These disorders weaken the structural "glue" of the body, which could make the cartilage more prone to abnormal growth. |

| Biomechanical Forces | Some theories suggest that imbalances in the forces exerted by the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles during growth could contribute. The constant pulling and movement during breathing might influence how the ribs and cartilage develop, especially if there's an underlying weakness. |

| Growth and Development | The most significant changes almost always happen during periods of rapid growth, especially puberty. Hormonal changes are believed to trigger or accelerate the overgrowth of the costal cartilage, which is why a mild indentation in a child can become much more pronounced in a teenager. For more technical insight, the NHS Scotland overview is a good resource. |

Essentially, while the overgrown cartilage is the direct culprit, these underlying genetic and developmental factors create the perfect storm for the condition to emerge.

Understanding these foundational elements helps explain why the severity of pectus excavatum can vary so much from one person to another and sets the stage for a deeper look into the associated conditions and treatment options.

The Genetic Link to a Sunken Chest

If you have pectus excavatum, chances are you've looked around at your family and wondered if you see a similar chest shape in a parent, sibling, or cousin. That's no coincidence. There's a very strong genetic thread running through this condition.

While it doesn't follow a simple inheritance pattern like eye colour, pectus excavatum absolutely runs in families. In fact, studies have shown that up to 40% of people with the condition have a close relative with a similar chest wall deformity.

This tells us that certain genetic traits are being passed down that predispose a person to the cartilage overgrowth that causes the sternum to sink inwards. It's like being handed a set of building plans for your chest that has a known tendency to develop in a particular way.

Connective Tissue and Its Critical Role

To really get to grips with the genetic link, we need to talk about connective tissue. Think of it as the body’s essential scaffolding. It’s the material that provides structure and support for everything – your skin, bones, blood vessels, and, crucially, your cartilage.

Imagine trying to build a house with a batch of faulty concrete. Even with perfect blueprints, the final structure is going to have weak spots. It's much the same with our bodies. If there's an underlying genetic issue affecting the quality of the connective tissue, the body's structural integrity can be compromised.

We see the clearest evidence for this in several genetic syndromes known for affecting connective tissue, which are also strongly associated with pectus excavatum.

The presence of a connective tissue disorder doesn't just increase the risk of pectus excavatum; it fundamentally changes how the cartilage behaves. It makes the chest wall far more likely to bend and deform under the normal pressures of growth during childhood and adolescence.

Common Associated Genetic Conditions

Although many people have pectus excavatum without any other underlying syndrome (we call this "isolated"), a significant number of cases are a feature of a broader genetic condition. The two most well-known are:

- Marfan Syndrome: A disorder of the connective tissue that affects multiple systems in the body, including the skeleton, heart, and eyes. People with Marfan syndrome are typically very tall and slender with long limbs, and chest wall deformities like pectus excavatum are a classic sign.

- Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes (EDS): This is a group of inherited disorders that impact connective tissues, most notably the skin, joints, and blood vessel walls. People with EDS often have hypermobile (overly flexible) joints and fragile, stretchy skin. The inherent weakness in their cartilage makes them much more prone to developing pectus excavatum.

There are other conditions we look out for as well:

- Loeys-Dietz Syndrome: A condition with features similar to Marfan syndrome that affects connective tissue throughout the body.

- Osteogenesis Imperfecta: Better known as "brittle bone disease," this condition can also affect the development and strength of the chest wall.

- Noonan Syndrome: A genetic disorder that can cause a wide array of distinctive features and health issues, including an unusually shaped chest.

The bottom line is that for a subset of patients, an underlying genetic condition is a major contributing cause. Uncovering this link is vital because it often means other parts of the body, like the heart and major blood vessels, need careful monitoring. This knowledge completely changes how we approach the overall management and treatment plan for that person.

Why Growth Spurts Can Worsen Pectus Excavatum

It’s a story we hear all the time from parents. A mild, almost unnoticeable dip in their child’s chest suddenly deepens and becomes much more obvious during their teenage years. This isn’t your imagination – it’s a classic feature of pectus excavatum, and it’s directly tied to the adolescent growth spurt. The very same biological surge that makes a teenager shoot up in height can make their chest indentation dramatically worse.

The answer lies in the costal cartilages, the pliable strips of tissue that connect your ribs to your breastbone (sternum). Even in a mild case, these cartilages are often genetically programmed to overgrow. When puberty hits, the body is flooded with growth hormones, which essentially put a foot on the accelerator for all bone and cartilage development.

For a teenager with the underlying traits for pectus, this hormonal signal tells the costal cartilages to grow far too quickly and excessively for the space they have available.

The Trellis and the Vine Analogy

Think of it like a vine climbing a garden trellis. In normal circumstances, the vine grows steadily, and the trellis supports it perfectly. But what if you gave that vine a super-fertiliser, causing it to grow at a phenomenal rate? It would quickly become too long and heavy for its frame, forcing the trellis to strain, buckle, and bend under the pressure.

This is a fantastic way to picture what’s happening inside the chest. The ribs and sternum are the ‘trellis’, and the costal cartilages are the ‘vine’. During that rapid growth spurt – usually between the ages of 11 and 14 in the UK – these cartilages grow so fast they literally run out of room.

With nowhere else to go, the overgrown cartilage forces the sternum—the most flexible point in the central chest wall—to buckle inwards. This mechanical force is the direct reason why the condition gets so much worse during puberty.

The result? A chest that was only slightly indented can become a deep, highly visible depression in just a few short months. Understandably, this rapid change can be alarming for teenagers and their parents, but it is a well-understood part of the condition's natural development.

The Hormonal Catalyst

The hormonal changes during puberty are the key driver here. These hormones don't just trigger changes in height or the development of adult features; they have a powerful effect on the entire musculoskeletal system.

This whole process really underlines why keeping an eye on the chest during childhood is so important. What looks like a minor cosmetic quirk in a nine-year-old could easily be the first sign of a condition that will become much more significant as they hit their teens.

Understanding this link between growth and severity is critical for knowing when to seek advice and how to time any potential treatment. It’s no coincidence that this is the exact time when most families come looking for answers, as the physical changes finally become too obvious to ignore.

Understanding Associated Health Conditions

Pectus excavatum rarely shows up alone. When we dig into what’s causing the sunken chest, we often find other health conditions tagging along. This is a critical part of the diagnostic puzzle because these related issues give us major clues about the body's overall structural integrity.

There's a common misconception that these other conditions are complications caused by the pectus deformity. In reality, they're more like fellow travellers, likely stemming from the same underlying weakness in the body’s connective tissues. Imagine a building constructed with slightly faulty mortar; you might see cracks in a few different walls, but they all share the same root problem.

When we see conditions like scoliosis or mitral valve prolapse alongside pectus excavatum, it strongly suggests a systemic issue, not just a problem confined to the chest wall. Getting this right is absolutely essential for a complete and accurate medical evaluation.

Common Musculoskeletal Companions

Since the root cause often involves the body's fundamental building blocks, it’s not surprising that other parts of the skeleton can be affected. The spine, in particular, is a common site for related changes.

- Scoliosis: This is where the spine develops a sideways curve, looking more like an 'S' or a 'C'. A significant number of people with pectus excavatum—some studies suggest up to a third—also have scoliosis.

- Kyphosis: You might know this as a 'hunchback' or rounded upper back. Kyphosis can also appear with a sunken chest, and the combination can really exaggerate a slouched posture.

These spinal issues and the pectus deformity are like two branches growing from the same tree. Both are shaped by the same genetic and developmental forces that influence how cartilage and bone grow throughout the torso. When we plan treatment for one, we always have to consider the other.

The Heart and Connective Tissue Link

The connection between pectus excavatum and certain heart conditions offers one of the strongest clues pointing towards a connective tissue disorder. The heart's valves are made of flexible, strong connective tissue—the same stuff that makes up the cartilage in the chest. If that tissue is inherently weaker or more 'stretchy' than it should be, problems can crop up in both places.

Mitral Valve Prolapse (MVP) is a classic example. It's a condition where the valve between the heart's left chambers doesn't close quite right. We see it far more often in people with pectus excavatum and other connective tissue disorders, which reinforces that idea of a shared, body-wide weakness.

While MVP is often mild and doesn't cause any symptoms, spotting it is a big deal clinically. It acts as a flag, prompting us to do a full cardiac workup to make sure nothing else is going on. This is a standard and vital part of any comprehensive pectus evaluation.

Taking a Broader Diagnostic View

Recognising these associated conditions is so important because it shifts our focus. We stop looking just at the chest and start assessing the person's health as a whole. A pectus excavatum diagnosis, especially when it comes with these other signs, might be the first step towards investigating a more fundamental genetic syndrome.

This table breaks down some of the most common conditions we see alongside pectus excavatum and explains how they're connected.

Common Conditions Associated with Pectus Excavatum

| Condition | Brief Description | Connection to Pectus Excavatum |

|---|---|---|

| Scoliosis | A sideways curvature of the spine. | Both are musculoskeletal deformities that often appear together, pointing to a shared vulnerability in the torso's structural tissues during periods of rapid growth. |

| Mitral Valve Prolapse | A heart condition where the valve flaps don't close smoothly. | The valve leaflets and the chest cartilage are both made of connective tissue. An underlying weakness can cause both MVP and a sunken chest to develop. |

| Marfan Syndrome | A genetic disorder that affects the body's connective tissue. | Pectus excavatum is one of the classic skeletal features of Marfan syndrome, which causes widespread issues in the heart, blood vessels, and skeleton. |

| Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes | A group of genetic disorders affecting connective tissue, often leading to hypermobile joints. | The weakened, overly flexible cartilage in people with some types of Ehlers-Danlos makes them much more susceptible to chest wall deformities like pectus. |

Understanding this network of related conditions empowers you to have much more informed conversations with your doctor. It ensures your evaluation is thorough—looking beyond the chest to check the spine and heart—and leads to a complete picture of your health and the best possible plan for managing it.

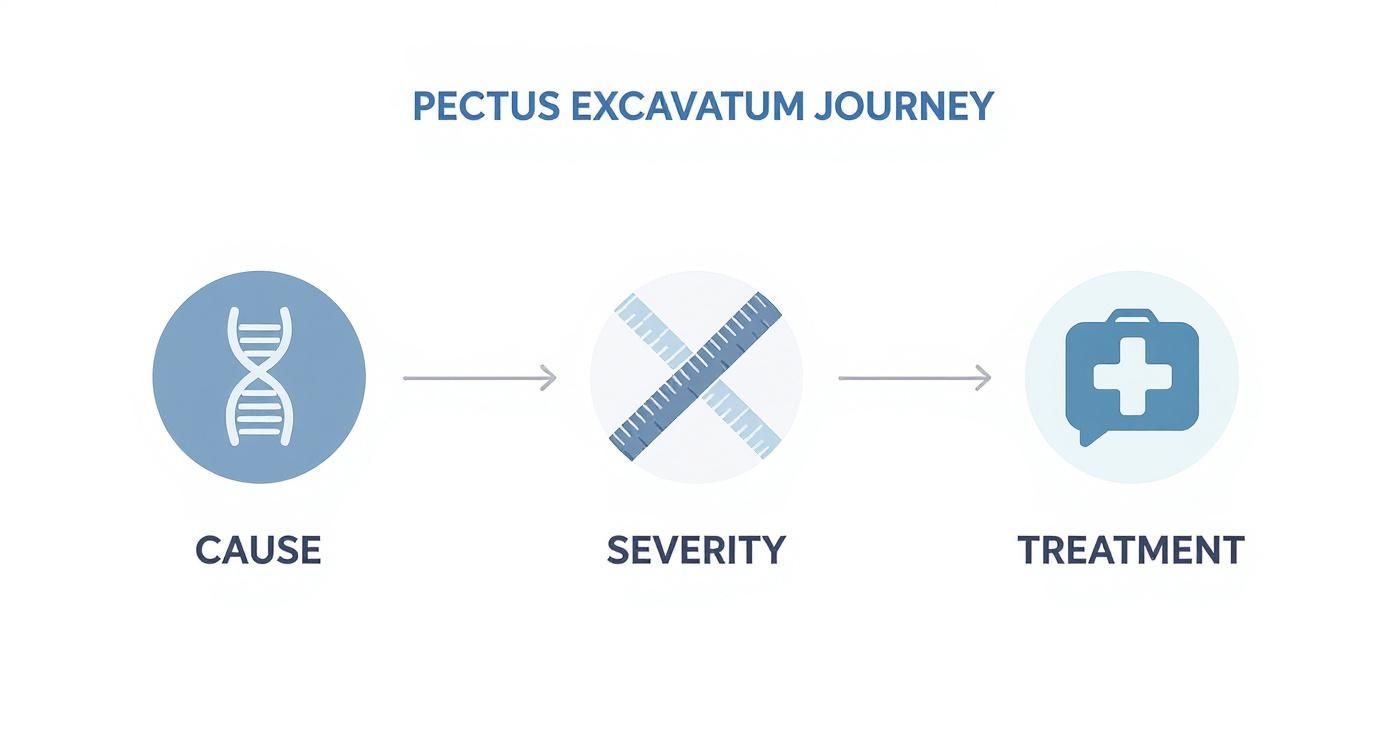

How the Cause Shapes Symptoms and Treatment

Figuring out what's causing an individual’s pectus excavatum isn't just a clinical curiosity; it's the bedrock of any treatment plan. The "why" behind a sunken chest directly shapes how it affects the body and what we should do about it. It’s the difference between just looking at the dent and truly understanding the whole person.

Think of it this way: a case of pectus excavatum that stands alone is managed very differently from one linked to Marfan syndrome. With Marfan, we're not just looking at the chest wall. We need a team, including a cardiologist, to keep a close eye on the heart and aorta because the underlying connective tissue weakness creates risks far beyond the shape of the sternum. Knowing the root cause tells us what else we need to look for.

From Cause to Clinical Assessment

Once we have a sense of the underlying cause, the next step is to get objective. We need to measure the deformity's severity and see what effect it’s having on the heart and lungs. This is about more than just what the chest looks like.

In the UK, the gold standard for this is the Haller Index. It's a simple ratio calculated from a CT scan that compares the chest's width to the distance between the breastbone and the spine.

A normal chest has a Haller Index of about 2.5. When that number climbs above 3.25, we consider the pectus excavatum to be severe. This isn't an arbitrary number; it’s the point where we often see the heart and lungs being squeezed for space. This measurement gives us the hard data we need to move forward.

Matching the Treatment to the Patient

There’s no "one-size-fits-all" solution for pectus excavatum. The right approach is always carefully matched to the person's age, how severe the indentation is (often guided by that Haller Index), their symptoms, and the underlying cause.

Here’s a look at how different situations are typically handled:

- Mild, Asymptomatic Cases: If someone has a slight dip in their chest with no breathing or heart issues, invasive treatment is almost never needed. The focus is usually on physiotherapy to improve posture and build core strength, which can make a real difference to the chest's appearance.

- Moderate Cases: For teenagers who are still growing and have a more noticeable indentation, non-surgical options like the vacuum bell can be a good choice. It's a device that uses gentle suction over many months to gradually lift the sternum.

- Associated Conditions: It's common for a sunken chest to be accompanied by other issues like severe rib flaring. When that's the case, we need a combined approach. Our detailed guide covering rib flaring treatment and surgery explains this in more depth.

The goal is always to align the intensity of the treatment with the severity of the problem. We start with the most conservative options and only consider more significant interventions for those with clear functional problems or a severe deformity.

Navigating Surgical Options in the UK

When pectus excavatum is severe and causing significant symptoms—like shortness of breath, chest pain, or an inability to keep up during exercise—surgery is often the most effective solution. The two main operations are the Nuss procedure (a minimally invasive repair using a curved metal bar) and the modified Ravitch procedure (a more traditional open surgery).

However, getting these procedures on the NHS has become a real challenge. Pectus excavatum is fairly common, affecting around 1 in 400 people in the UK, especially boys. Despite this, routine NHS funding for surgical correction was stopped in 2019. The reason given was a need for more evidence on long-term benefits versus costs. The British Association of Paediatric Surgeons has more information on this decision and its impact.

What does this mean for patients today? For most, NHS surgery is now only available through an Individual Funding Request (IFR). This is a tough process that requires proving an "exceptional clinical need," a bar that is often very difficult to clear. Because of this hurdle, many families find themselves turning to the private sector for a timely assessment and treatment, allowing them to address the condition before it has a bigger impact, both physically and psychologically.

Navigating the Diagnostic Process in the UK

If you or your child have a sunken chest, your first port of call in the UK is always your GP. It can be hard to know when to make that appointment, but a few key signs should prompt you to get it checked out. Things like getting out of breath more easily during exercise, chest pain, or simply noticing the dip in the chest is becoming more obvious are all good reasons to book in.

Your GP will start with a physical check-up, looking at the chest wall and asking about your symptoms and whether it runs in the family. This initial chat is really important. It helps the GP decide if a referral to a specialist thoracic service is needed for a closer look.

It’s worth remembering that pectus excavatum is the most common chest wall deformity we see in the UK. Some older research suggests it affects around 1 in every 126 people. It often really makes its presence known during the big growth spurt in puberty, usually between 11 and 14 years old, and it’s about four times more common in boys than girls. You can read more about the prevalence and characteristics of this condition in this detailed study.

What to Expect from a Specialist Assessment

Once you get that referral, the specialist team will organise a few more tests to get the full picture. This isn't just about what your chest looks like on the outside; it’s about digging deeper to see how the shape is affecting your heart and lungs on the inside.

Think of it like a full mechanical check-up. The team needs to quantify the severity and understand its real-world impact on your body's engine room.

- CT Scan: This gives us a brilliant cross-sectional view of the chest. From this scan, we calculate the Haller Index – a vital measurement that compares the chest's width to the narrowest point between the breastbone and the spine. It’s the gold standard for objectively grading how severe the dip is.

- Echocardiogram: This is essentially an ultrasound for your heart. We use it to see if the heart is being squashed or pushed out of position by the sternum. It also lets us check for related issues, like mitral valve prolapse, which can sometimes be linked to the underlying cause of the pectus.

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs): These are a series of breathing tests that measure your lung capacity and airflow. They tell us in black and white whether the sunken chest is physically restricting your ability to breathe properly.

This journey—from exploring the cause to measuring severity and deciding on treatment—is a well-trodden path.

As you can see, a proper diagnosis isn’t just a glance at the chest. It’s a process that connects the dots between potential genetic links, the physical measurements of the deformity, and the right path forward for treatment.

Understanding NHS Pathways

The results from these tests give us the evidence we need to map out what comes next. It’s important, however, to be realistic about the current situation for pectus treatment on the NHS.

While these diagnostic tests are readily available, getting approval for surgical correction is another matter. It’s become very challenging and usually requires an Individual Funding Request (IFR), which has an incredibly high bar for approval. Because of this, many people want to understand all their options. This comparison guide of the NHS and private sectors can be a helpful starting point. No matter which route you end up taking, this initial diagnostic work-up is the foundation for everything that follows.

Your Top Questions About Pectus Excavatum Answered

Even after understanding the main causes, it's natural to have more specific questions pop up. Let's tackle some of the most common ones we hear from patients to clear up any lingering confusion and bust a few myths.

This is all about giving you direct, practical answers to what's on your mind.

Can Bad Posture Cause Pectus Excavatum?

This is probably the most frequent question we get, and the answer is a straightforward no. Bad posture does not cause pectus excavatum. The condition is rooted in how the cartilage grows deep inside your chest—an internal, developmental process that posture has no control over.

However, posture absolutely affects how pectus excavatum looks. If you slouch or have rounded shoulders, it can make the indentation seem much deeper and more obvious. This is exactly why physiotherapists often recommend exercises to strengthen your back and core muscles. While those exercises won't change the underlying bone and cartilage, they can dramatically improve your overall torso shape and confidence.

Think of it like this: your posture is the frame around the picture. A better frame won't change the picture itself, but it can make the whole thing look a lot better. Good posture helps you stand tall, which can minimise how noticeable the dip is.

If I Have Pectus Excavatum, Will My Children Inherit It?

There’s certainly a genetic component. We know that pectus excavatum can run in families, so if you have it, there is a higher chance your children might develop it too.

But, and this is a big but, it's not a guarantee. The inheritance isn't a simple coin toss. Plenty of cases just appear out of the blue, with no family history to speak of. This tells us that while genes load the gun, other developmental or environmental factors might pull the trigger. If this is a real concern for you, the best first step is to chat with your GP about your family history for more personalised advice.

Does Pectus Excavatum Always Get Worse Over Time?

Not always, but there's a key time to watch out for. The condition tends to become more pronounced during major growth spurts, especially that big one during the teenage years, usually between ages 11 and 14. The surge in growth hormones can accelerate the cartilage's abnormal development, causing the sternum to sink further.

Once you stop growing and reach skeletal maturity in your late teens or early twenties, the shape of the chest usually stabilises. At that point, it’s unlikely to get any worse on its own. In some very mild cases seen in young children, there’s even a chance it might improve slightly as their chest develops, but this isn’t typical for more significant indentations.

At Marco Scarci Thoracic Surgery, our goal is to give you clear, expert assessments so you can fully understand your condition and your options. If you have concerns about a chest wall deformity, we provide rapid access to consultations and create treatment plans designed for you. To arrange an appointment, please visit us at https://marcoscarci.co.uk.