Minimally invasive thoracic surgery has come a long way. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and robotic techniques have dramatically reduced pain, shortened recovery times, and improved cosmetic outcomes for our patients.

But not every case plays out the way we plan.

Sometimes, despite careful imaging, preparation, and technique, we have to pivot mid-procedure—and convert to an open thoracotomy.

This isn’t failure. It’s sound surgical judgment.

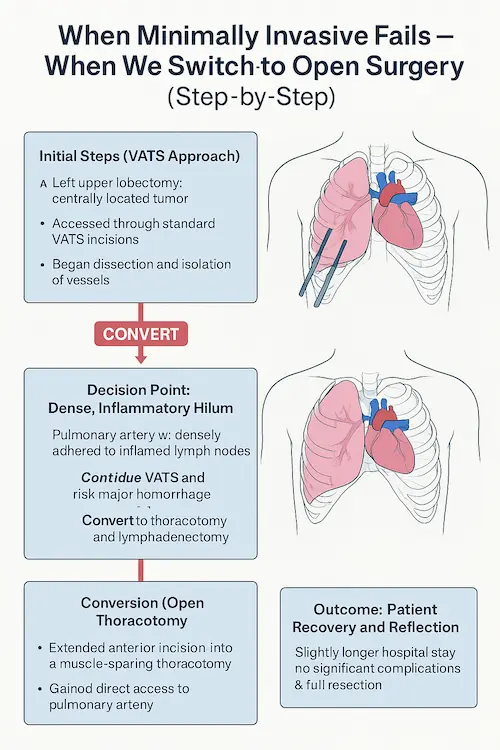

In this post, I want to walk you through a real case where a planned minimally invasive lobectomy became an open procedure. I’ll share the decision points, trade-offs, and how the patient did afterward.

The Case: Left Upper Lobectomy for a Centrally Located Tumor

The patient: 62-year-old male, smoker, with a 3.8 cm left upper lobe mass abutting the pulmonary artery. Imaging suggested it was resectable via VATS.

We planned a VATS approach to maximize recovery benefits and minimize post-op pain.

Initial Steps (VATS Approach):

- Access through standard three-port incisions.

- Good initial visualization.

- Dissected superior pulmonary vein and started isolating the pulmonary artery branches.

Decision Point 1: Dense, Inflammatory Hilum

What we saw was unexpected: the lymph nodes were rock-hard, matted, and fused to the PA.

Attempts at gentle dissection were met with bleeding from a small arterial branch. Controlled quickly, but it was a warning sign.

I paused and asked: “Can I do this safely through a scope, or am I gambling with vascular control?”

Trade-off: Continue VATS and risk major hemorrhage vs. convert to thoracotomy and gain control.

We converted.

The Conversion (Open Thoracotomy)

- Extended the anterior utility incision into a muscle-sparing thoracotomy.

- Gained direct access to the pulmonary artery.

- Dissected the inflamed tissue carefully and securely clamped the artery before dividing it.

That one move probably prevented a catastrophe.

We proceeded with the lobectomy and a full mediastinal lymphadenectomy.

What This Case Taught (and Reminded) Me

- Conversion is not a failure—it’s maturity.

The worst reason to avoid converting is ego.

- Vascular control is non-negotiable.

When you can’t confidently control the pulmonary artery, it’s time to pivot.

- You must decide before bleeding forces your hand.

Waiting too long increases risk. Most regretful conversions happen too late.

- Have the whole team prepared.

We always brief our anesthesiologist and staff: “There’s a 10% chance we’ll go open.” No surprises.

- Patients care about outcomes, not incisions.

I’ve never had a patient say, “I wish you hadn’t converted.” They care that we did what was safest.

Final Thought:

Minimally invasive surgery is an incredible tool. But a thoracic surgeon’s most powerful skill isn’t the ability to operate through tiny holes—it’s the wisdom to know when not to.